Concrete the Conflict!

Here’s an example (from the wonderful Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier) of how theme and conflict can often best be conveyed by character action and interaction with concrete elements of the setting.

CONCRETE THE CONFLICT

Here’s an example (from the wonderful Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier) of how theme and conflict can often best be conveyed by character action and interaction with concrete elements of the setting.

Here, the new bride finds a book that Maximilian’s late wife had given him as a gift, with her name scrawled on the frontispiece.

The book is a concrete object that can be handled and moved. It’s a stand-in or a symbol for the dead wife—the one that Maximilian won’t speak of and obviously can’t forget.

Read how the new bride interacts with the book, carefully cutting out the page with Rebecca’s writing, as if this would be like cutting Rebecca’s memory from Max’s mind.

There was the book of poems lying beside my bed. He had forgotten he had ever lent them to me. They could not mean much to him then. "Go on," whispered the demon, "open the title page; that's what you want to do, isn't it? Open the title page." Nonsense, I said, I'm only going to put the book with the rest of the things. I yawned. I wandered to the table beside the bed. I picked up the book. I caught my foot in the flex of the bedside lamp, and stumbled, the book falling from my hands onto the floor. It fell open, at the title page. "Max from Rebecca." She was dead, and one must not have thoughts about the dead. They slept in peace, the grass blew over their graves. How alive was her writing though, how full of force. Those curious, sloping letters. The blob of ink. Done yesterday. It was just as if it had been written yesterday. I took my nail scissors from the dressing-case and cut the page, looking over my shoulder like a criminal.

I cut the page right out of the book. I left no jagged edges, and the book looked white and clean when the page was gone. A new book, that had not been touched. I tore the page up in many little fragments and threw them into the wastepaper basket. Then I went and sat on the window seat again. But I kept thinking of the torn scraps in the basket, and after a moment I had to get up and look in the basket once more. Even now the ink stood up on the fragments thick and black, the writing was not destroyed. I took a box of matches and set fire to the fragments. The flame had a lovely light, staining the paper, curling the edges, making the slanting writing impossible to distinguish. The fragments fluttered to gray ashes. The letter R was the last to go, it twisted in the flame, it curled outwards for a moment, becoming larger than ever. Then it crumpled too; the flame destroyed it. It was not ashes even, it was feathery dust... I went and washed my hands in the basin. I felt better, much better. I had the clean new feeling that one has when the calendar is hung on the wall at the beginning of the year. January the 1st. I was aware of the same freshness, the same gay confidence.

The door opened and he came into the room.

From Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

--

See how much more effective that is than just telling about her jealousy and insecurity. Notice how meticulously the action is narrated—how carefully she cut the page, how it burned. That helps bring the scene to life, and dramatizes the conflict.

Then the use of the page helps build the theme of the inescapability of the past. The book and writing become motifs (the recurrent images or patterns which help create the theme) of the permanence of past and memory.

Also, using an actual object as a symbol allows for all sorts of tricks like subtext and foreshadowing—the fire destroying the page foreshadows the fire that destroys their house and lives later in the book.

So think about a scene where you have a complex emotion or conflict. What is an object in the scene which can be used as symbolic or thematic in some way? What’s a plausible way the character can interact with it and make use of it?

Best writing!

Alicia

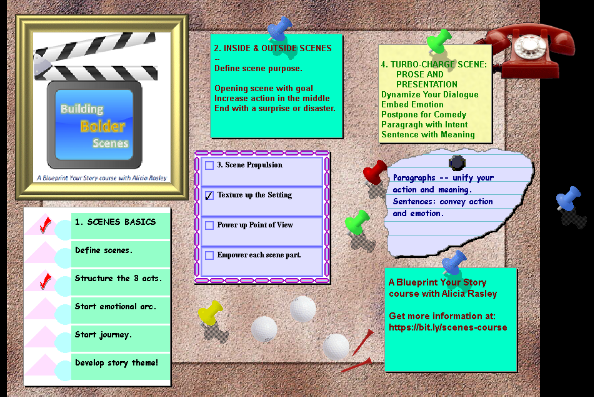

So if you're interested in reading more about the Scenes course and joining, here's the link again: http://bit.ly/building-bolder-scenes

Feel free to share this with any writer friends. And have fun writing! And let me know if you have any questions!

Alicia plotblueprint@gmail.com

Setting Up the Setting in the Scene with ONE SENTENCE

Just in time for our Scenes Course, here’s a short discussion of setting up your setting (time/place) in the first paragraph of your story!

Setting Up The Setting: ONE SENTENCE c. by 2021 by Alicia Rasley

One of the purposes of the opening few paragraphs is to establish the setting. If the reader is going to embark on this fictive journey, he needs to know where we are, and when we are, right? We can establish the larger setting with a tagline after the chapter heading:

Topeka, August, Sunset

June 1815, Waterloo

... if we want to-- that quickly establishes the overall limits of this world. But for the opening SCENE, how do we efficiently and evocatively establish where and when we are?

How about some sample lines that might appear in your own story's first couple paragraphs and tell the reader where this first scene is taking place, where and when the characters are?

The late afternoon light filtered in through the dirty store window.

New snow was piled another inch deep on the windowsill outside.

(Windows are useful because they show both inside and outside.)

Across the ballroom was a set of French doors, an escape out to the torchlit gardens.

To connect this to the character and event, maybe make the POV character do the perceiving, and react to it in some way:

Jamie squinted at the statue in the middle of the square, distinguishing through the glare of the noon sun the outline of a general on a horse. Gotta love England and its fixation on long-ago wars.

New snow piled up three inches deep on the windowsill outside, and Sarah pulled her shawl tighter.

Miss Carter stood in the doorway, surveyed her new kingdom, and started coughing. The early morning classroom smelled like chalk, pencil shavings, and teenaged hormones.

Across the ballroom was a set of French doors, Harry's escape out to the torchlit gardens.

This doesn't have to be done in all one sentence, of course, but I like to get clear early a few of these:

Where we are

Are we inside or outside

What time of day it is

Is it dark or light

What time of year it is or at least whether it's cold or hot

The POV character

That character's relation to the setting (Harry wanting to escape the ballroom)

Are there other people around

What it feels like there (stuffy or cold or crowded)

What's going on (a dance, a substitute teacher arriving, a chess game)

What the sound is like-- noisy, quiet

I find the last element harder to get in (sound), I guess because the opening is so often primarily visual. Hmm. Maybe sound is a good "entree"-- after all, often we hear before we see. Smell is very intrusive. So is sound:

Margaret closed her eyes to ward off the glare of the sun. She wished she could close her ears to keep out the sound of the chain saw butchering her old beloved oak tree.

Anyway, look at the first paragraphs of your own story, and maybe you can sneak in something, a line or two, that can establish "where and when" without getting out of the story?

Alicia www.aliciarasley.com www.plotblueprint.com Sign up for my email list for writing information.

If you're interested in the Building Bolder Scenes course, let me know!

here's the link again: http://bit.ly/building-bolder-scenes

What Harry Potter Can Teach Writers about the End of the Character Journey

Want to create an intense experience for the reader?

Start at the end! Craft the emotionally right end of the character journey.

Consider this: If your readers have gotten all this way to the end of your story, they know your characters and they know your story about as well as you do. Well, maybe not quite as well (but in some ways, maybe better!). Consciously or subconsciously, they know what the characters need. And they know what the story needs for a satisfactory ending, though they might not be able to articulate this.

But if you give them the wrong one in the end—an ending that does not complete the main character’s journey- their disappointment and dissatisfaction will be evidence that you did it wrong. So the ending – well, you have to get that right to know you’ve achieved a satisfactory experience for the audience.

What Harry Potter Can Teach Writers about the End of the Character Journey

By Alicia Rasley

Want to create an intense experience for the reader?

Start at the end! Craft the emotionally right end of the character journey.

Consider this: If your readers have gotten all this way to the end of your story, they know your characters and they know your story about as well as you do. Well, maybe not quite as well (but in some ways, maybe better!). Consciously or subconsciously, they know what the characters need. And they know what the story needs for a satisfactory ending, though they might not be able to articulate this.

But if you give them the wrong one in the end—an ending that does not complete the main character’s journey- their disappointment and dissatisfaction will be evidence that you did it wrong. So the ending – well, you have to get that right to know you’ve achieved a satisfactory experience for the audience.

Let’s examine this “journey” idea in a very long story that most of you know: the Harry Potter series. Each of the seven books of course stands on its own. In each book, young Harry has a journey, but also the entire series works together as what they call a coming-of-age story –a bildungsroman. So there’s also a “series journey” for Harry, so that each of the books becomes a section of the longer journey.

In this pair of articles, we can discuss Harry’s journey, first through the initial book, and then through the entire series.

As you know, Harry starts out in Book 1 being raised in the household of a family of "Muggles," non-magicals like us ordinary people. But most importantly he's an orphan, who like one of the orphans in a Charles Dickens story is abandoned and neglected. He's not really abused—his aunt and uncle take care of his basic needs. But he is neglected, and he knows that no one loves him. The parents who did love him are dead in a shady and perhaps shameful way, so no one will speak of them. In fact, he doesn't actually even know if they loved him. All he knows is that they died.

And then—in this important first act of the story—Harry meets a talking snake and a cake-carrying giant, and he embarks on a journey to find himself and his place in the world.

Here are some lessons novelists can learn from Harry’s first journey.

1. The first “journey” lesson from Harry Potter: Identify the journey, and use that to provide a structure for the whole story.

In this first book, his journey starts in invisibility. In that first book's opening, Harry is so invisible that he sleeps under the stairs. He is so invisible the neighbors don't even know exists. He's so invisible that his aunt and uncle who take care of him won't even acknowledge that he's there, don't send him in to school, don't celebrate his birthday.

But during the book, Harry has to make the journey from invisibility in the ordinary world to belonging in the wizard world. In the end, he takes up his rightful place in that world—which, because he is “the boy who lived,” an almost mythical creature, is as something of a star.

2. Show the journey start in the opening of the story.

That is crucial. At the start of the story, the reader doesn't know your character and can't intuit what the journey start is. So show it, as JK Rowling shows his invisibility, how he is hidden away, how he almost doesn't exist. Make it concrete for the reader. How invisible is Harry? Well, he's so invisible, he has to sleep in a closet! He's so invisible the neighbors don't know he exists! That's showing invisibility, which we all know is more effective than telling.

It’s a good idea to start this first stage of the journey early. When the Harry series opens, there’s only a short prologue where Harry is a baby, then the Dursleys take him and effectively disappear him. Don't spend more than a chapter or two setting up the start of the journey. Then create an "inciting incident" which either forces the character to act, or gives him/her a reason to start changing (the snake at the zoo speaks to Harry and makes him realize he’s got some secret power).

3. Have the plot lead the character further into the journey and force change.

Once you come up with a character journey like “from this starting point to that destination,” you can deepen the story by connecting the character’s emotional/psychological changing to the events of the external plot. So: While Harry’s family desperately tries to keep him invisible, the wizards enforce their rule that wizard children must go to Hogwarts for school. That’s the beginning, and that’s when Harry starts to realize maybe he’s not “no one”—he’s someone, and he’s got a place here.

There’s a brilliant scene that really plays with “invisibility”, when Harry uses his father’s invisibility cloak not to disappear, but to explore Hogwarts and learn more about his new home. On this venture, he finds in the Mirror of Erised, which shows him his greatest desire—the first image of his dead parents. Very clever-- the cloak of invisibility lets him see without being seen—and then the mirror reflects back what he doesn’t know he wants—an essential step on the journey of taking OFF his invisibility and joining into the wizard world. Notice this scene is placed in the middle of the journey—that is, when Harry should be growing away from that starting point. When he realizes he can be invisible and then take that cloak off and be himself, he has taken a major step to the destination of belonging to this new world.

4. Then let the ending show in some concrete way that the character has achieved the destination of the journey—and what has changed in life.

Here, the first book ends with Harry certain that he belongs; in fact, he and his new best friends have won Gryffindor the coveted annual cup, and he knows he will be coming back here for his second year.

But he has a new realization, that with this new life come new responsibilities. When he was “invisible” at the Dursleys, he didn’t matter. No one depended on him. He could go through life as a mopey and secretly defiant pre-teen. Now here at the end, he belongs, he has a place in the world, and he also has responsibility. What he does matters, and now he can’t be careless and apathetic.

In fact, he’s realizing that with his visibility as “the boy who lived,” he has a special role in fighting against Lord Voldemort. While he was invisible, hidden with the Dursleys, he was safe, if unhappy and lonely. But now at Hogwarts, he has a home, friends, a purpose—and a new, lethal enemy.

Let’s try that with your own story! Think of your central character. You might have more than one main character, but let’s just concentrate on one for the moment. Creating a character journey will help unify your story and also deepen your texture by developing the character along with the plot events.

So here are just a couple questions to help you focus on your character journey and how it will work, especially in the opening and ending of the story. I’ll use the Harry Potter example to illustrate:

1. So where does your character start, and where does he/she end up?

Harry starts out unwanted, invisible even to himself, and ends up belonging in a new world and truly knowing who he is.

2. What internal resonance does this have-- how does the journey change who this person is?

Harry learns who he is—a wizard- and what he can do –magic-, and also that he was and is loved. This gives him confidence and meaning.

3. List a few steps your protagonist will have to take to complete this journey:

He must leave his home and venture to Hogwarts.

He must learn who and what he is.

He must make friends and allies.

He has to also learn about his parents’ death and who caused it.

He has to show how he has earned his new place in this new world.

4. How is the starting point shown in Act 1?

His foster family has been hiding him for years. No one acknowledges his birthday or tells him about his parents.

5. In Act 2, what event(s) force the character into rising conflict around this journey issue?

Harry confronts several challenges, both the mundane (school) and the exotic (the troll), and can only surmount them by gaining friends and trusting them to help him. But then he finds that the true danger is hidden within the school itself, and in his own past. So he must figure out what this all has to do with him by going into his own past and learning about the tragedy of his parents’ death.

6. In Act 3, how does the completion of the journey help this character resolve the external problem (and/or vice versa, how does resolving the external problem help the character complete the journey)?

Harry completes his journey to belonging and knowing himself. This allows him to use his powers and his new alliances to defeat Voldemort (temporarily) and rid Hogwarts of the enemy hidden within. Once he has done all that, he is truly accepted into his new world.

7. Any other thoughts or questions about your character’s journey?

It’s important to SHOW the journey, not just explain it. So there are concrete and immediate ways to show Harry’s journey start (hidden under the stairs, neglected by guardians) and ending (winning the “cup” at the end of the school year, cheered by his schoolmates).

YOUR TURN!

Now of course, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone is just the first book in a long series. And Harry has a longer journey to travel, for which this is just the first step. So in Part 2 of this article, we’ll look into the journey of Harry through the series of stories, which is a deeper and more universally important journey—from Denial of Death to Acceptance of Death. A philosopher might even say that this isn’t just Harry’s journey, but the journey of the whole human race as we strive to deal with the knowledge of our own mortality.

This might be helpful to you if you plan a series of linked stories and want to create a thematic unity from Book One to Book Last!

Harry Potter’s Journey, Part 2, will be coming in a couple days. In the meantime--

--

Here’s my exploration of Journey, with several good examples from students and stories you’ll know!

Braiding the Character with the Plot:

THE CHARACTER JOURNEY with Alicia Rasley

https://aliciarasleywritersjourney.blogspot.com/p/the-character-journey-alicia-rasley-i.html

Also, if you’d like to learn more practical and yet sophisticated techniques to deepen your story and intensify your audience’s experience, you might be interested in my new course Building Bolder Scenes.

You can sign up here to get notified when it’s ready to launch in a couple weeks!

Get notified about my new scenes course: http://bit.ly/scenes-course-info

Scene Planning and Design Specs by Alicia Rasley (c. 2021)

Scenes are what give the reader the experience of the action of the story and the perspectives of the main characters. Without scenes, the story would be heard and not experienced-- told but not shown. They are the generators of plot change and character development. And they're what the reader remembers long after she's forgotten the names of the characters or the details of the plot—the vivid moments of story captured in action.

Scene Planning and Design Specs by Alicia Rasley (c. 2021)

Scenes are what give the reader the experience of the action of the story and the perspectives of the main characters. Without scenes, the story would be heard and not experienced-- told but not shown. They are the generators of plot change and character development. And they're what the reader remembers long after she's forgotten the names of the characters or the details of the plot—the vivid moments of story captured in action.

First, let's define "scene' and some aspects of it.

What is a scene? A scene is a unit of action and interaction taking place more or less in real-time and centering on some event of plot development.

The important elements are:

Action– Something is happening! There is movement and progress and change during this time. Where there is action, there is danger of some kind.

Interaction– The viewpoint character is interacting with other characters and/or the environment. This will cause sparks. The interaction will force more action on the viewpoint character.

Real-time– A scene usually takes place in a continuous span of time, with a starting point and an ending point. This sounds basic, but it's essential. Unless the reader sees the action unfolding (that is, not in retrospect or summary), she will lose that important sense that this event is really happening.

Event– Every scene should center on an actual event, something that happens– not a dream, not a flashback, not a passage of introspection. A character is doing something, experiencing something, not just in her own mind, but in the external reality of the story. That can mean she's taking an action, discovering a secret, encountering another character, having a conversation, creating something new, enduring a trauma– but you should be able to identify what event has taken place in this scene.

Plot development– Events are important because they are concrete and real and have consequences. Most important, they have consequences on the plot. This event, this scene, should cause a development in the story.

All this adds up to CHANGE. At the end of the scene, the characters and the plot should have changed in some increment. It doesn't have to be a major change (although turning point scenes will lead to major changes)—just a change of some sort.

Now I don't think most writers actually plan every scene. Sometimes scenes are magically generated, top to bottom. I'm thinking of my own experience... scenes come to me when I'm lying in bed in the morning half-asleep. It's something between dream and creation-- directed dreaming, only it's much more coherent than any dream.

That sort of inspiration/dreaming/imagination/subconscious stuff works well early in the writing process. Big scenes, important scenes, come to me, and I learn all sorts of things about my characters and plot just "viewing" these scenes in my head.

The problem is, we can't rely on magic. The majority of scenes have to be invented because they're just not "inspired".

And that's where scene-planning comes in-- for all those scenes in-between, the workhorse scenes, the ones that get the characters from here to there, ones that we have to think up! Even a few minutes of planning-- determining the scene purpose, the POV-character or scene-protagonist's goal, the conflict, the central event, and the "surprise" at the end-- can make the scene meaningful.

So let's try planning your scene before you get started writing it. Just answer these questions to give you an overall sense of the purpose and progress of the scene.

~~~~0~~~~

Design Specs:

1. Give this scene a temporary name that identifies the main thing that happens.

Example: the "Max Mugging Scene," because, natch, what happens is Max gets mugged.

2. When and where does the scene start? When and where should it end? How long a span of time is that? How long a distance in space?

Example: The scene starts early in the evening—dusk- as they are walking through Soho to Covent Garden. It ends about an hour later, when it's fully dark, and right back there where the mugging took place. So it's about an hour later, but the same spot.

3. What do you want to change in this scene—in the plot, emotionally, in the characters' understanding, or…

Example: I want Max to end up with a broken leg so that he misses his dad's company banquet.

4. Who would be the best "narrator" or point-of-view character for this scene? Why?

Example: I want Val to narrate the scene as that's who is going to come to a realization about Max.

5. What is the character's immediate goal at the start of the scene?

Example: Val has been given the assignment of sneakily preventing Max from getting to the banquet where he would probably just get drunk and make a scene, which his dad the boss doesn't want.

6. Is that goal going to be fulfilled by the end of the scene?

Example: Yes, Val keeps Max from going to the banquet, but feels guilty because Max got hurt.

7. What's the main conflict or problem in the scene?

Example: Maniac Max and Nebbishy Val don't understand each other at all, but Val's job is keeping Max out of trouble.

8. What's the central event of the scene?

Example: Max gets mugged, and Val has to intervene to save him.

9. What's the surprise at the end of the scene?

Example: Val returns to the scene of the mugging, and finds a clue that implicates Max's dad's private security force.

Okay! You have the scene designed… Now read over your plan, and then just start to write!

If you're interested in the Building Bolder Scenes course, let me know! You can sign up here to get an announcement when it's next ready for enrollment.

https://www.getdrip.com/forms/976436646/submissions/new

First sentence in the scene- Starting the experience

First sentence in the scene —

Starting the experience…

I’m having some fun creating a big Building Bolder Scenes course, and now I’m focusing on the mechanics of creating the scene experience with the sentences and paragraphs. Scenes are EXPERIENCES, not just recountings. So getting the experience started early—the first sentence!—can set the reader up to FEEL all the way through.

Just keep in mind that your reader is apprehending the scene holistically-- she's incorporating every detail, not just your character's thoughts and feelings, into her experience. So you can imbed emotion subtly in the description and action. Just remember not to overdo. But yes, you can use adjectives and adverbs here. Just don't use them when you don't need them ("shouted loudly, bright scarlet"), and then when you DO use them, they'll have more effect.

You can set the stage early, hint at that "beginning emotion" of the emotional arc of the scene, by anchoring the setting in the first paragraph or so... but meaningfully. Here are some examples of how to sneak in emotion with physical/setting detail in the first paragraph of the scene:

LIGHT

His bulky body filled the entrance and blocked most of the afternoon light.

She shielded her eyes against the harsh noon light and squinted at the broken window.

He parked in the pool of yellow light from the streetlamp and slowly got out of the car.

She woke when the dawn light sliced through the curtains. Nothing had changed.

He squinted to see through the dimness in the barroom, searching the dark booths for the woman he had lost.

The car brakes skidded on the gravel, and when they finally stopped, the moonlit lake was only a few feet from their front bumper.

TIME OF DAY

The Angelus bells were ringing when she started across the muddy field towards the church.

She woke suddenly. The red glowing numbers on the bedside clock read 2:04. It took her a moment before she realized she had missed her flight.

He was going to be late for work again. Again.

All she wanted to do was rush home and be halfway through a quart of Java Chip ice cream before American Idol came on.

INSIDE/OUTSIDE

She pushed the porch door open and stood there a moment, drinking in the view and the crisp mountain air.

Jamie woke up cold and damp on the bare open ground.

I knew this place—the kitchen looked familiar and unpleasant.

Patty rubbed the condensation off the passenger-side window and looked out at the snowdrift. "How stuck are we?" she asked.

He put his fork down on the dining room table and grimly called the family to order.

The old barn stood alone on the hill.

The road gravel infiltrated her sandals, and she was limping and lost by the time he found her.

It was a lady's parlor, all dainty and tidy, and he didn't think he better sit down on any of the little chairs.

AIR

The barroom smelled of ground-out cigarettes and spilled beer.

She zipped up her parka and pulled on her gloves, took a deep breath, and stepped out the door into the howling Chicago winter.

From the lantern-lit park pavilion across the river drifted the lazy strains of a dance band.

The library was so overheated every breath felt like she was sucking in a blanket.

It was going to snow. She could taste it with every crystalline breath.

Not a breeze stirred the evening air, and she hesitated with her hand on the gate.