Hi, everyone! I was asked to do a guest post about what I call "Life Hooks"—the recording of memories that lets us yank our life experiences together.

I've never had much of a memory. We moved around a lot when I was young, so every year I'd be in a new place and all those visual cues to memory (the chair my grandmother sat in, the kitchen where I started a fire while making popcorn) were left in the old place. But years ago, for my parents' 50th anniversary, I was in charge of making up a "memory book" of old photos. There are eight of us siblings, so I delegated each a town the family had lived in along the way, with the assignment of choosing some photos associated with that place and writing down a memory. What I learned from that process is that we each remember different things, but also different sorts of things. I regret to tell you that what I remember are old grievances (like the time my big brother told me to do a swan dive into the snow off the back porch in Elgin, IL, assuring me that it would just be like jumping onto a big pillow: Note to self, never trust a big brother's assurances). Mark (that very big brother) remembered the cars we had, and since my dad would buy old junkers that couldn't last, he had to remember a lot of them. Rick, the youngest, remembered a single crystalline experience of going out into the desert and seeing the stars like they'd just burst into flame. We all remembered… but different things in different ways.

What I also learned was that the very fact of recording a memory brought up a dozen more, and that as my parents paged through the memory book, they recalled events and experiences none of us had ever heard of. It was as if they could live them again—and significantly, they remembered only happy things, or at least things that were amusing in retrospect. The memories weren't lost, but they needed a "hook" to become accessible. And that hook was the sharing of our collective memories.

As we baby boomers move protesting and incredulous into our senior years (btw, I just saw a book title, "You're Never Too Old to Rock and Roll," which could be our battle cry), I think we're going to need to find more of those memory hooks. We were most of us more dedicated to keeping our options open and trying new things to get much into ritual and tradition, which are the most common ways of "hooking" memories. Many of us have moved far away from our homes and families, discarding boxes of junk and mementos on the way. Now we look back at a lifetime and find that we don't have a lifetime's worth of memories available for review. But of course we do. Experience carves actual pathways through our brains—that's where the memories are stored—and we have them, but it's like they're up on a high shelf in a distant corner of a dusty attic in an abandoned house. We need a way to find them and bring them back into the light of life.

After doing the memory book, I realized that there's something special about the physical representation of memory. I used to scorn my friends who scrapbooked; now I wish I'd been doing that all along, saving the tickets from concerts and films, the cards I'd gotten for my birthday, the scraps of my life which I just threw away. I know now that the act of recording events, capsulizing them into some piece of paper or photo or memento, and gluing them into a book, would hook my memories together. And then they'd always be right there—not so much in my mind as in this physical book, ready to be taken down and paged through whenever I need a reminder of who I used to be.

What is it about an actual book and actual ink and actual photos? I wonder why those are still so significant in these digital days—why we still jot down a to-do list in the morning, rather than just texting ourselves our schedule; why we page through a young couple's white satin wedding album when we've already seen the photos posted on Facebook.

Maybe the physical act of recording captures the physical experience? My sister-in-law Cher Megasko, a frequent traveler, keeps a travel journal and writes down her impressions as she makes each trip. She said, "I journal when I travel abroad, taking care to record lots of unremarkable details. I keep track of each drive we take, every restaurant we eat at ... even things like the number of stray dogs and cats. I'm surprised at how often I go back and read what I've written. Sometimes it's just to reminisce, but I also use it to help plan future trips, even if not to the same destination. My travel journal is my younger daughter's first choice of things to inherit when I'm gone!"

The memoirist and writing teacher William Zinsser echoed the importance of both the recording of the unremarkable, and the usefulness of a physical representation: "When my father finished writing his histories (of the family and his shellac company), he had them typed, mimeographed, and bound in a plastic cover. He gave a copy, personally inscribed, to each of his three daughters, to their husbands, to me, to my wife, and to his 15 grandchildren, some of whom couldn’t yet read…. I like to think that those 15 copies are now squirreled away somewhere in their houses from Maine to California, waiting for the next generation."

My friend Cynthia Furlong Reynolds has also used the physical to capture the ephemeral memories. She once worked to help elderly people record their memories—kind of making their own oral histories-- and told me that they often found it oddly calming. She remembered sitting with one elderly man with dementia, taking notes as he talked about his past. Then she typed up her notes and made them into a little book, which she printed out for him. She tells me his wife found that when he got agitated, just holding the book of memories calmed him. I think it's because knowing the memories were in this paper-and-ink, permanent form freed him from the anxiety that he might forget. He didn't have to constantly remind himself about his childhood home, or his mother's name. All that was here in this book and would always be there for him.

Maybe all this "physical" stuff is just a relic of any earlier age… but I don't know. I had two nieces who are close in age – still teenagers-- but not in geographic proximity, and while of course these days, they kept in touch with texts and emails and Facebook messages. But once we were all together, and they showed me the little wooden boxes where they kept the letters they mailed to each other (yes! envelopes and stamps and all), and here they were, children of the electronic era, holding these pieces of paper and reading the letters out loud and remembering when they'd written them.

Anyway, I'm thinking of printing out some of those photos I have on Pinterest, writing out a note to my mother-in-law by hand for once, maybe even getting a scrapbook and starting—way too late!—to collect the junky little scraps of my days and nights. Maybe then, when my always-bad memory slides into no-memory-at-all, I'll have something to touch and page through that reminds me I indeed did have a life!

What do you think? How do you hook into your memories? How do you remind yourself of what's been and gone? What do you want never to forget?

I'll leave you with a couple pretties to help jog your memories—

Here's a Tim Buckley song about memory, Once I Was.

And a W.B. Yeats poem, "When You Are Old and Gray and Full of Sleep (take down this book)."

Alicia Rasley

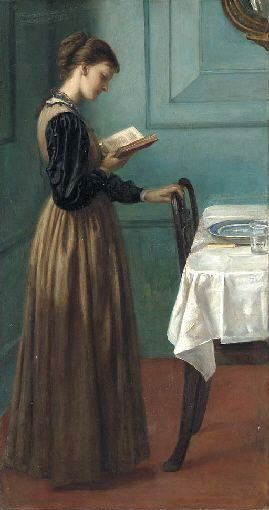

My grandmother Alice Pustek in front of the cottage they built in Beverly Shores, IN.